Belonging Here

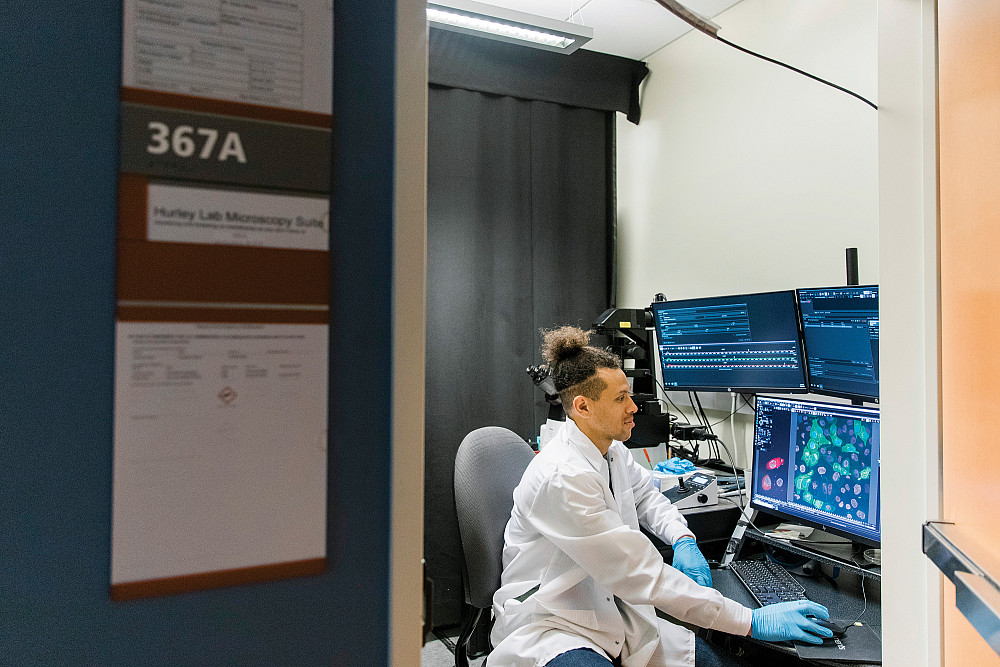

At UC Berkeley, Aaron Joiner’12 is doing important research on the protein structures implicated in two neurodegenerative diseases, including ALS. His commitment to that work and to helping younger scientists of color feel at home in his field attracted a major honor from Beloit last fall.

As a high school senior who grew up in South Beloit, structural biologist Aaron Joiner’12 wasn’t initially sure Beloit was right for him. He wanted to “go far away” to college and see the world beyond Southern Wisconsin. Second, he had already logged many hours on Beloit’s campus by participating in a local chapter of Upward Bound while on the cusp of being a first-generation college student. Then, among the many scholarship offers he had to choose from, he earned one for full-tuition at Beloit.

“I was grateful to have the opportunity to attend university more than anything else, but I was slightly unsure whether I was making the right decision to stay so close to home,” he says. “I ended up absolutely loving every minute of my time at Beloit.”

Once on campus, Joiner, well, joined. He played intramural frisbee, basketball, and volleyball, and participated in varsity track and field, captaining the team for two years. He was also involved with student government and Tau Kappa Epsilon fraternity, volunteered for Habitat for Humanity, and studied abroad in Spain. All of this was on top of being as pre-med as one can be at a liberal arts college.

“It provided me with a lot of good time-management skills and being able to juggle many things without letting anything drop,” he says. Since then, he’s gone on to build a successful career as a research scientist, earning his Ph.D. from Cornell University in 2020 and now working as a post-doctoral researcher at the University of California-Berkeley. In fall 2022, he received a high honor from Beloit’s Alumni Association: the Young Alumni Award.

Organic chemistry professor Laura Parmentier was one of Joiner’s Beloit academic advisors and remembers him with vivid fondness. “He stands out in my mind as one of those students who was motivated, but also really kind and thoughtful and just a delight to spend time with,” she says. A memory stands out — one day he appeared at her office door carrying a tray of her favorite frosted sugar cookies. She adds that his trajectory from a first-generation college student to successful scientist is impressive. “He created his own path and is now doing great things as a scientist and as a human being, with his strong advocacy work in training and mentoring other first-generation students and students of color,” she says.

To M.D. or not to M.D.

During a summer medical school prep program at the University of Louisville in Kentucky after his sophomore year at Beloit, Joiner got to see what it was really like to be a physician, a profession his family had encouraged him to enter.

He was able to shadow doctors and learn the nitty gritty details of practicing medicine. Immediately after that program, he went on a semester abroad in Alicante, Spain. “The timing of those two things was quite critical,” he says. “I had spent the summer figuring out what it would mean to be a physician, and then I was away from external influences — family, friends, expectations, and was forced to sit and reflect on my own.” It was there that he realized being an actual medical doctor — “not the TV version” — wasn’t for him.

But it wasn’t until his last semester at Beloit during a career advising day that he discovered a life in biological research — with a sponsored graduate degree — was a possibility. Always one to test the waters before diving in, after his Beloit graduation, Joiner embarked on a six-month research internship at the Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute in Panama City, Panama. It solidified his desire to pursue a career in scientific research.

A sense of belonging

When he started the graduate program in biochemistry, molecular, and cell biology at Cornell University, Joiner, who is Black, quickly realized he was in an extreme minority. “I would look around in my classes the first few years and be like, ‘Oh, I’m the only Black student in this classroom,’” he says. “Certainly, it made me wonder: ‘Do I belong here? Why did they invite me into this program?’”

He knew he wanted things to change at the school, for himself and future students of color. “Having to ask those questions undercuts your confidence and weighs on you like a dark cloud that is always bogging you down a little bit,” he says. “Even if it’s 5 to 10 percent of your mental energy, that adds up when you could be spending it thinking about your research questions or something more productive.”

Over time he met other students who felt the same way. “We had our own little critical mass, agitating and making noise about the environment,” he says. They were joined by a supportive supervisor and other allies. “I was able to build a community around trying to improve the environment so future Ph.D. students wouldn’t have to feel the way that I did or overcome the same hurdles that I had to tackle,” he says. He also collaborated with New York’s Science and Technology Entry Program (STEP) to start a shadowing program for under-served high school students to learn about higher education and careers in scientific research.

At some point, Joiner heard an episode of the “PhDivas Podcast” about imposter syndrome — something he had been grappling with at Cornell. “The show reframed it in a way that changed it completely for me,” Joiner says. “Instead of questioning whether you belong and whether you fit into the system, remember that many systems in our country, including academia, were built to exclude people of color by design. And rather than questioning how you fit in, think of yourself as a spy who has infiltrated this system, and you’re learning as much information as you can to navigate and survive and to pass on to other people. That frameshift for me was really helpful.”

In 2020, he graduated from Cornell with a doctorate in biochemistry as a Dean’s Excellence Scholar and with an Exemplary Service Award, among other honors. In 2022, he was selected as one of 25 Hanna Gray Fellows by the Howard Hughes Medical Institute, a fellowship designed to support exceptional and diverse leaders in biomedical research.

A complex problem

Credit: Alison Yin

The field that ultimately spoke to Joiner was structural biology — the study of how biological molecules are built. “It was a field that made sense in my head,” he says. Since 2021, Joiner has been a post-doc in the Hurley Lab at UC Berkeley. “I’m trying to see what a protein looks like, how it’s built, and how its structure allows it to do a specific job inside of a cell,” says Joiner.

Learning how healthy cells function on the micro level can help us understand what happens when macro things go wrong in human bodies. The field is growing in two areas, each informing the other. One is observing how proteins interact with each other in groups. “We’ve been capturing larger and larger complexes of proteins, [asking]: ‘What is the architecture of these proteins when they come together to perform a task? And how does the way that they come together allow them to do their job?’” says Joiner.

The other direction involves observing the intricacies of proteins in their native ecosystems. Thanks to recent advances in the cameras used to capture images, proteins no longer need to be removed and studied in a test tube, but rather can be observed within cells where they normally reside.

Joiner’s work focuses on three proteins implicated in two neurodegenerative diseases — Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis (ALS or Lou Gehrig’s Disease) and Frontotemporal Dementia (FTD), the disease the actor Bruce Willis was recently diagnosed with.

“My job at the moment is to try to understand what these proteins are doing normally in cells that are happy and healthy and functioning,” Joiner says. “And once we can figure that out, we can hopefully understand how, when these proteins are not doing their job, that plays into these two neurodegenerative diseases.”

Embracing failure

Though his lab work is satisfying, working to increase diversity in the sciences continues to be important to Joiner. Mentoring has been logistically challenging since he began his new role during the pandemic, but he’s been able to guide grad students in his lab. One of the main things he aims to teach is that the path of scientific research is exciting, but also hard and filled with mistakes and failure. “I try just to be supportive in whatever way they need,” he says. “Oftentimes it’s realizing that research is difficult, and it fails many more times than it succeeds, but it’s not a personal reflection on them, it’s just that things are difficult and that’s OK — you’ll learn from the failure.”

He gives himself the same advice he offers mentees: “What we’re doing is hard. If it weren’t difficult, we would have all the answers already,” he says. “We are literally working at the edge of what we know about biology, which is very complicated. There are tens of thousands of proteins in a cell, and they’re all interconnected, so trying to tease apart one or a few of their individual contributions to cellular health and homeostasis, it’s really tricky — even if your experiments all go perfectly well.” Which, as every scientist knows, they often don’t.

Credit: Alison Yin

Another bit of advice he dispenses to himself and others: Spend time out of the lab! “I think a lot of people don’t necessarily remember to try to stay happy and try to do things outside of the lab,” he says. This summer, he’s training for a DIY triathlon. (“I don’t like to pay for races,” he chuckles.) Some parts of it he’ll bike with friends from Beloit and grad school. His wife, Alexandra Hinck’14, may also run some with him. He and Hinck, a social scientist and assistant professor at San Francisco State University, met during his junior year at Beloit when they were on the track and field team. In 2019, during a visit to their Midwest alma mater, they got engaged; they married in July 2022 in Grand Rapids, Michigan.

The couple travels, gardens, and rockclimbs together — and they also bake. Joiner’s Twitter bio reads: “Delighted by exercise, chocolate chip cookies, and protein structures.” His go-to cookie is one that he bakes himself — “The Worst Chocolate Cookie Recipe” (Google it and discover how it earns its name). Does his science brain measure each grain of flour by the nanogram? “That’s what a lot of people think,” he says. “But the problem is I spend all day in the lab following protocols, following recipes, essentially, so by the time I get home I don’t want to do that.”

Valerie Reiss’95 is a writer and editor based in Western Massachusetts. You can read more of her work at valeriereiss.com.