Fridays with Fred - Iron City

“Professor Who Wrote ‘Book of Chaos’ Resigns: Beloit College Head Denies Censorship” – The Chicago Tribune, March 21, 1920.

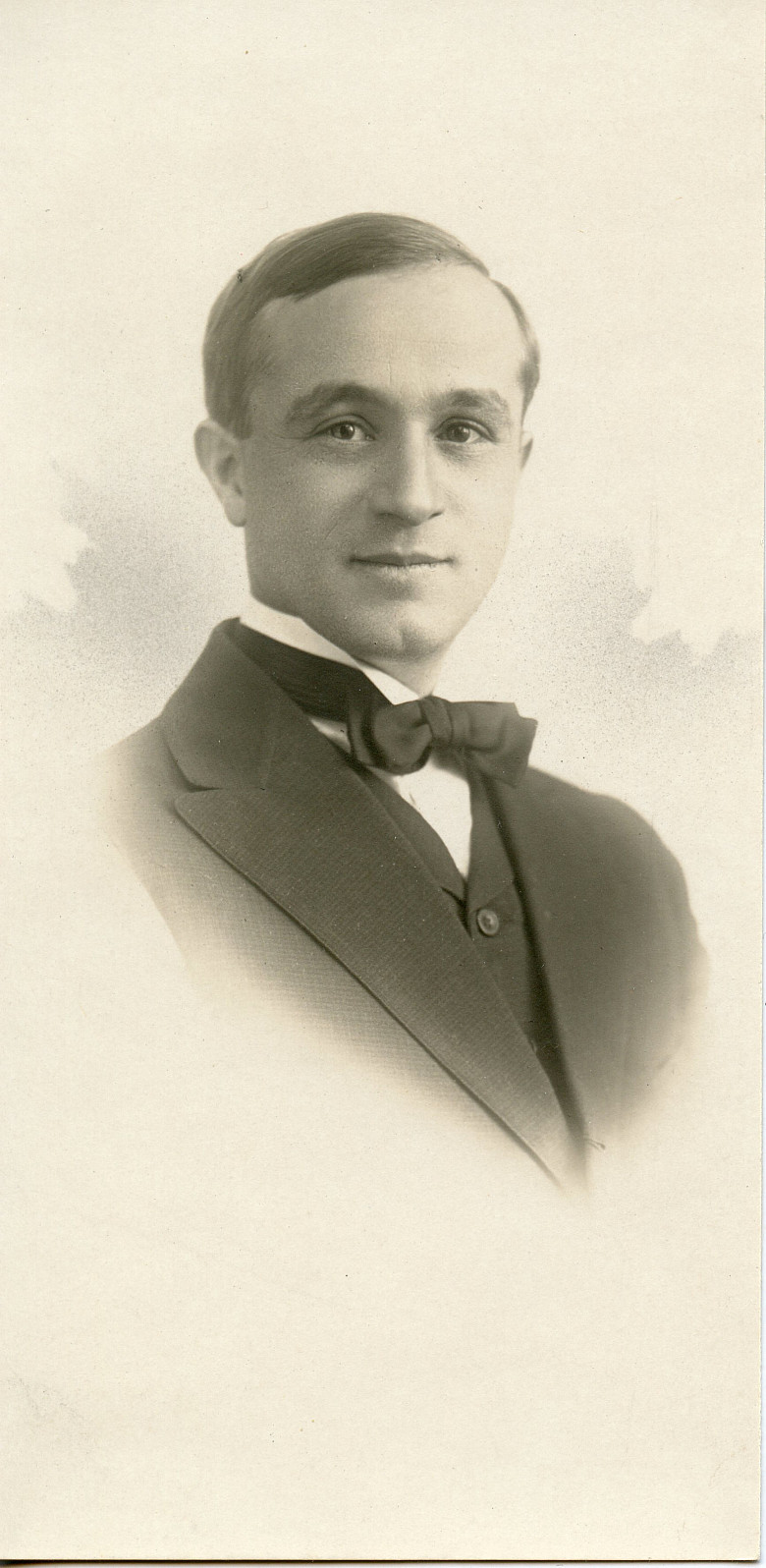

The professor was Marion H. Hedges, a young man of diminutive stature and outsized personality. His novel, Iron City, damaged relationships between the college and city powerbrokers, provoked the resignation of a beloved professor, and either angered or entertained Beloiters who flocked to the city’s bookstores for copies. In the end, Hedges, voted by students the college’s most popular professor, would leave Beloit in disgrace and never teach again.

Marion Hedges, a DePauw University graduate from Winamac, Indiana, was just 25-years-old when he began teaching English and journalism at Beloit in 1913. He quickly immersed himself in college activities, chaperoning student parties, bowling and playing tennis with fellow faculty, founding a new campus literary society, and organizing a local chapter of the journalistic fraternity Sigma Delta Chi. He wrote publicity pamphlets for the college and contributed a column to the local newspaper. But he began to gain notoriety with his co-founding of the “William Morris Club,” a branch of the Intercollegiate Socialist Society, and did not endear himself to the college establishment when he seemed at ease discussing campus problems with students.

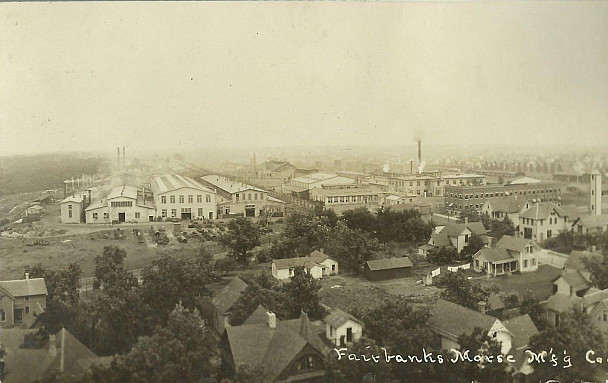

Although Hedges published frequently in literary magazines, he held grander ambitions. While a keen observer of day-to-day life at the college, he also studied Beloit history and society, especially the struggles of working-class people, many of them immigrants, toiling in local factories. He conceived of writing a novel illustrating the closedmindedness of a hidebound college and depicting the tensions between factory owners and workers resulting in a strike and the crushing of a labor union, while also describing the coming of age and disillusionment of a young college instructor. He employed Beloit and himself as fodder for Iron City. Beloit College became Crandon Hill College. Beloit Iron Works became Crandon Hill Iron Works. Fairbanks-Morse and Company became R. Sill and Son. And Marion Hedges became the novel’s hero, John Cosmus.

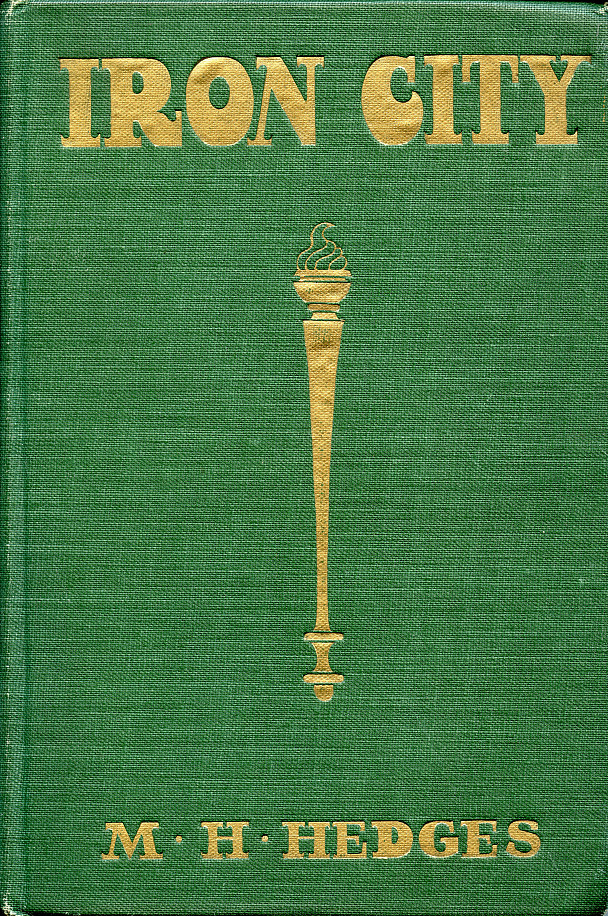

Literary critic Randolph Bourne wrote to Boni & Liveright, a risk-taking publisher, later famous for being the first to publish Faulkner, Hemingway, Freud, and E. E. Cummings, among others. “Iron City is the strongest first novel I have ever read,” Bourne said, “and I consider it to be one of the few really great American novels.” Boni & Liveright accepted the novel and published it in September 1919 to generally favorable reviews which often touted the author’s promising literary future.

Two years before, Melvin Brannon had become the third president of Beloit College, succeeding Edward Dwight Eaton. Unlike his two clergyman predecessors, Brannon was a scientist and administrator who instituted “progressive” curricular changes, including semi-professional and pre-vocational programs. To a young radical like Marion Hedges, Brannon’s statement that “a reasonable liberalism, properly guided, is essential for the world’s progress” was a welcome change.

Hedges gave the president an advance copy of Iron City, which Brannon praised to the Beloit Daily News: “[Iron City is] a courageous and direct attack on the inability of college education to take a dynamic hold on the world. Unless we can have an open door policy in discussing intimately these things which are in all men’s minds and hearts, we may as well write failure on the door of the entrance of civilization.”

And, under the headline, “Prof. Hedges is Author of Strong Novel,” the paper announced Iron City’s publication before the book reached local stores and provided comments by the author. “In Iron City,” Hedges declared, “I have embodied the results of ten years’ study of American life, and it is this background of national culture against which the story moves.”

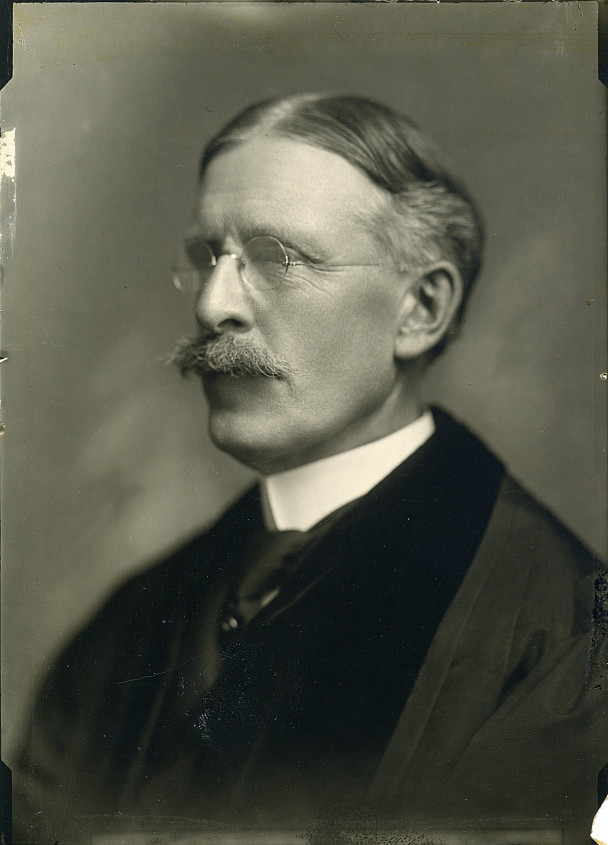

He left unsaid that he had used Beloit as his model. Once Beloiters began to read the novel, they recognized people, places, and events, sometimes lampooned, more often skewered. For example, Crandon Hill College president, Hugh Crandon, was a dead ringer for former Beloit College president, Eaton: “He was the dominating figure in Crandon Hill life. He looked his part, tall, square, alert, with gray hair and mustache, and a refined manner. His face had lost, if it ever had possessed it, anything of ministerial look; it wore an expression of calculating shrewdness…” Hedges didn’t leave it at that, adding, “President Crandon seemed utterly suspicious of an idea…The mind must have been an inward-opening storehouse, for no ideas ever got out. Cosmus often thought, if an idea could be properly sexed, clothed in immaculate linen, and presented at an afternoon tea, or at a meeting of the board of trustees, then Crandon might accept it, especially if it appeared with proper references… The old, the tried, the well-bred—these must be the custom of the college…”

Professor Robert K. Richardson, who had begun teaching History at Beloit in 1901 and was beloved by generations of students, considered himself a member of the “old guard,” which Hedges believed was stodgy and out of touch. While on leave that semester, Richardson read Iron City and noted: “Some of my own private conversation [with Hedges] is repeated.” He also revealed that a setting in the novel was remarkably like a real place: “Even the pictures are accurately described as they hang in the room.” What surely angered Richardson most was Hedges’ description of Crandon Hill College History professor, Charles Henry Clarke: “Of all his colleagues, Clarke stuck Cosmus as the strangest specimen of the academic mind; he always thought of him as a medieval Tory, if there were Tories in the middle ages. The psychology of Clarke was beyond his comprehension. How he could daily interpret the radicals of the past, and daily reject the radicals of the present, Cosmus could not see. It seemed to Cosmus that Clarke considered the middle ages a kind of Utopia from which mankind had moved forward like a crab.”

Richardson reacted to the novel and Brannon’s praise of it by tendering his resignation. Many of his longtime colleagues sympathized. Professor of Religion John Pitt Deane wrote: “…I need not say that I am profoundly disappointed in it. You know that I have always found Hedges stimulating and have believed in him. This, although I know his impatience with the church and most social institutions. I have attributed that to his earnest interest in the poor and the disadvantaged…I know that it was probably written for a purpose, probably to jar something loose, to compel thought. But what possible excuse can there be for the parody and caricature of the local situation and of the men with whom he is professionally associated?”

Venerable professor, Almon W. Burr, spoke for his fellow “old guard”: “We are weathering the storm that the Iron City has brought. It has struck pretty deep into Beloit, alienated some of the College’s best friends. I am still deeply indignant over it. I call it crude, cruel, crass and carnal. I would not have this author teach another day in Beloit.”

Brannon and the Trustees rejected Richardson’s resignation and he taught at Beloit for another 30 years.

After Iron City’s publication, President Brannon felt heat from Beloit citizens, including powerful men from the city’s major industries, among them Alonzo Aldrich, president of Beloit Iron Works, a manufacturer of paper making machinery. Aldrich reflected the business community’s dismay over the college harboring radicals like Marion Hedges: “Most colleges have now connected with their staff of teachers, agitators that are as dangerous as any Bolsheviki or I.W.W. in the country; in fact, I think, more so, because they are genteel and therefore more insidious. I feel that every college should sever their connection with all such men as Mr. Hedges…I believe the fundamental and particular business of all colleges and the part of the curriculum that should be stressed, is the teaching of Americanism, Patriotism, and Loyalty…”

Brannon replied, mentioning the author’s value to the college and that the students had voted him most popular professor. He later described Hedges as “one of the most inspirational teachers on the Beloit College faculty, more than that, has few equals in America.” Aldrich would have none of it: “The ‘most popular man’ vote does not impress me, only perhaps as a warning. You know some of our most noted rascals were models in gentility and suavity.”

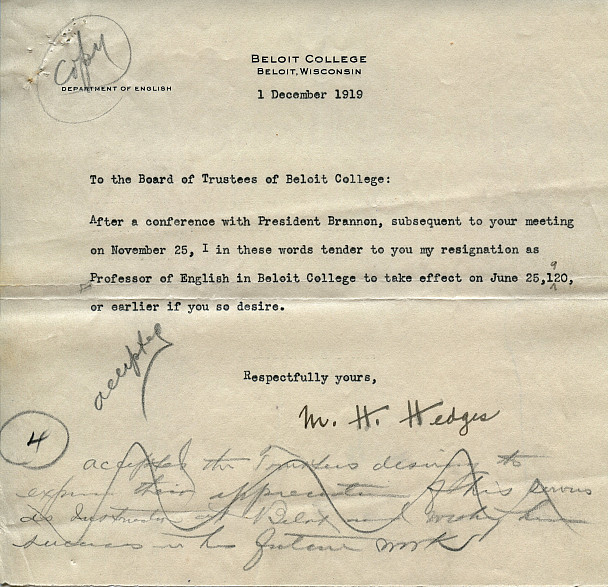

Marion Hedges must have realized that the fate of his fictional hero, John Cosmus, might be his own. While the social ostracism and subsequent “firing” of John Cosmus anticipated what befell Hedges, the author clearly believed he had something vital and worthwhile to say in Iron City. When he wrote of John Cosmus, “…It seemed more important to him that justice triumph than that his own body be comfortable,” Hedges likely provided a clue to his own character. The Board of Trustees accepted his resignation at their April 1920 meeting. Brannon told the Round Table how much he regretted losing Hedges and the paper praised him as “one of those rare men, best termed practical idealists.” Brannon also denied to the press that the resignation had anything to do with Iron City.

However, in later years, Marion Hedges insisted that he was pushed out and blacklisted from ever teaching again. He left Beloit for a position as special editorial writer for the Minnesota Daily Star, a radical free labor newspaper. According to a 1940 article in the Beloit Daily News, when Hedges departed, “after seven years on the faculty there had been only one staunch friend at the station to see him and his family off.”

Hedges pursued a varied and intriguing career after leaving the classroom. For a time, he continued his literary work, even publishing a second novel, Dan Minturn, in 1928. His passion, though, remained with labor reform, and from 1924 until his retirement 30 years later, he was an active trade unionist and labor lobbyist. For 23 years he worked as the supervising editor of the International Brotherhood of Electrical Workers’ IBEW Journal, and was the IBEW director of research. He passed away in 1959.

The 1919 edition of Iron City is available to read online at the Internet Archive, the Hathi Trust Digital Library, and at Google Books. In 1994, Beloit College Press republished Iron City and included two introductions about Hedges, the literary and historical value of his work, and the controversies surrounding it.