Fridays with Fred - the Eaton Chapel Fire of 1953

It was a couple of hours past sunset on December 12, 1953. Snow clung to the Middle College cupola and blanketed the Indian mounds. A few students were out and about, hunched against the chill breeze on their way to the Carnegie Library (WAC) or leaving lab work at the Pearsons Hall of Science. Earlier that day, students and faculty had gathered in the chapel, crafting decorations for Christmas Vespers, but they hadn’t finished. One of the students, Don Norenberg, was on his way back when he smelled smoke and then spotted wisps of it puffing up from the roof. He immediately called in an alarm. Eaton Chapel was on fire.

From the college’s founding, a chapel had served as a campus focal point. Faculty and students initially crowded into a single room in Middle College, but in 1858, the college constructed its third building, later known as South College, which would house a chapel on the second floor and an academy on the lower floors. As Beloit College grew, it needed a larger space for worship and for community lectures and other programs.

By 1891, the college had secured enough funds to build a new chapel and hired the Chicago architectural firm, Patton and Fisher. On January 26, 1892, Beloit dedicated the Richardson Romanesque-style chapel, constructed of square-stoned limestone and featuring a clocktower with bells that would chime a familiar melody for generations of students hurrying to classes.

The chapel remained without a name until 1930, when the college honored its second president, Edward Dwight Eaton. In 1938, the college modified the exterior and redid the interior, adding elegant new pews where men and women sat together for the first time, faculty joining them instead of perching on a raised platform.

Gazing upwards, visitors discovered a dazzling display of ceiling panels painted by Russian artist, Nickolai Kaisarhoff. The fifty panels presented early Christian symbolism designed in Byzantine style, featuring brilliant colors over a dull gold background. Dog-toothed Romanesque chandeliers hung from the ceiling. None of these cherished decorative embellishments survived the fire.

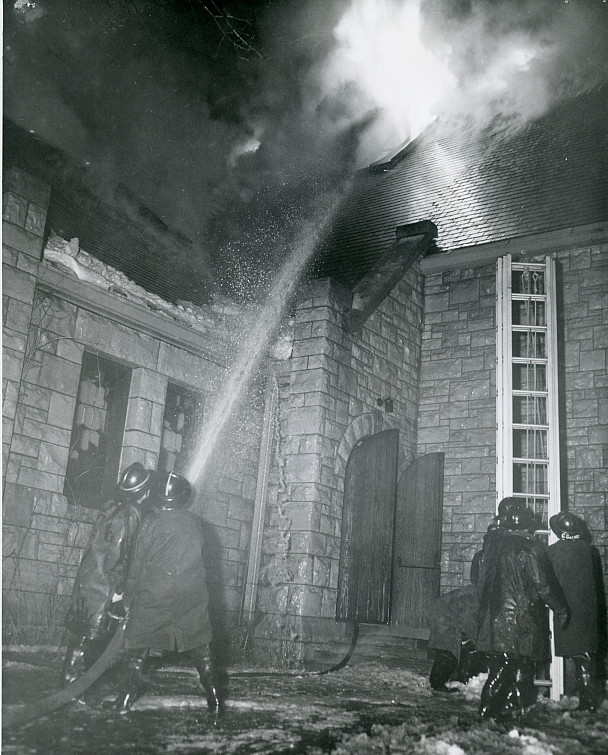

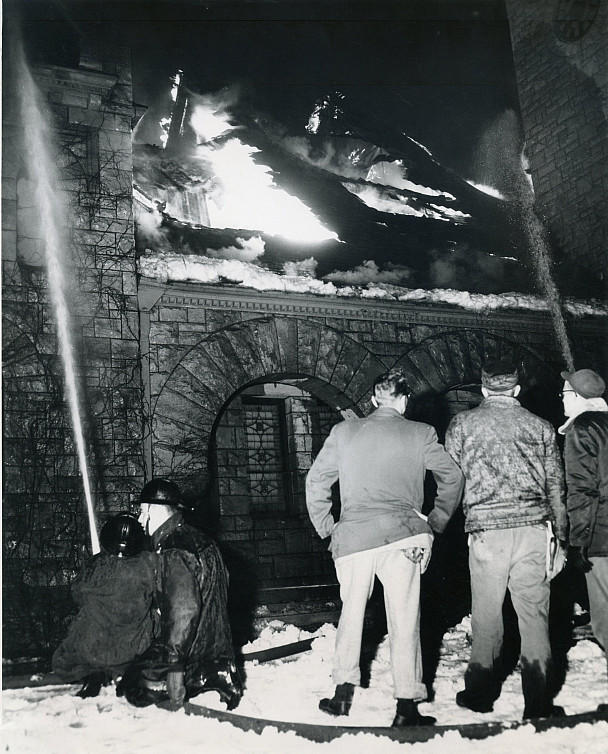

Sirens wailing, firetrucks sped to the chapel, now enveloped in thick smoke. Spectators also raced to the scene, some of them in fancy dress, gussied up for the Christmas Formal planned for the Field House that night.

Initially there were no flames visible and it seemed as if the firefighters would gain control quickly. However, fire spread within hollow pillars and suddenly shot out of windows and through the roof, which newspaper accounts described as an “inferno.” The Bulletin of Beloit College later reported: “Tears streamed down the faces of the coeds and the universal comment was ‘I never realized how much the Chapel had meant till now.’

This sentiment was sensitively phrased by the Rev. Chad Walsh of the English Department, preceding his sermon at Sunday evening Christmas Vespers services, when he said that students, alumni, faculty, and the entire community now realized that the Chapel had been the heart of the College.” Although many students resented the long hours spent on those hard pews, the chapel fostered a sense of community like no other building on campus.

The flames spread so rapidly and so thoroughly, there was almost no chance to rescue college relics or other precious items. In an era without copy machines, flash drives, or data clouds, a member of the faculty dashed into his basement office and grabbed the only copy of his unfinished doctoral thesis. Alas, another professor lost all of the books and research material he had planned on using for his doctoral thesis.

The overcrowded college library had stored 40,000 books in the chapel basement and lost most of them. Some one-of-a-kind college documents survived the fire, including ledgers of student grades dating as far back as the 1840s. They now reside in the College Archives, still scorched and soot-covered.

As firefighters concentrated on saving the bell tower and other exterior walls, Beloit College students helped place and hold hoses. One of them, a slim, dark-haired freshman named Steve, broke his glasses while helping push out a firetruck mired in deep mud. Steve also held a secret unrevealed until over a month later.

Throughout the night, as firefighters tried to tame the blaze, the chapel chimes continued to ring in each quarter hour.

The following day, bright sun shone on a roofless chapel, charred timbers, blackened pews, and soggy hymnals long ago edited by Edward Dwight Eaton. The fire had destroyed the valuable pipe organ, several pianos, new recording equipment, and all of the choir robes. The college faced a major decision, whether to raze the remaining walls or to attempt rebuilding Eaton Chapel. Well-wishers donated money and the college would receive $250,000 insurance money. The nearby First Congregational Church offered to host Vespers services. Meanwhile, fire experts tried to determine what caused the blaze.

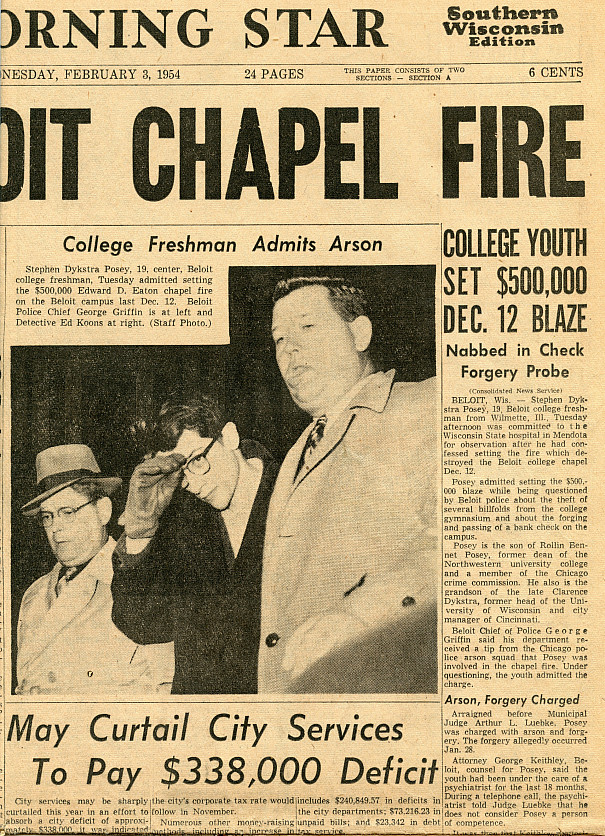

In early February of 1954, a psychiatrist tipped off Chicago police that one of his patients had admitted setting the chapel fire. Stephen Dykstra Posey was an 18-year-old Beloit College freshman.

Beloit police chief, George E. Griffin, took down Posey’s signed confession and told the press what apparently happened: “As a member of the college choir, he was in the chapel on the afternoon of Dec. 12, rehearsing for a Christmas concert the following day. After rehearsal he left to purchase some Christmas tree light bulbs, returning after the building was deserted. He inserted a lighted cigarette inside a book of paper matches and placed them on a shelf in a basement closet containing cleaning materials…the matches apparently flared up, igniting oily rags and setting fire to the building…” According to a 1965 interview with Professor Chad Walsh, Posey found inspiration for the incendiary device after seeing the 1953 film, Stalag 17.

Griffin noted that Posey joined other students in helping firefighters. “I did everything I could to put the fire out,” Posey told him. “I didn’t mean to start anything that gargantuous.”

Posey’s arrest prompted lurid headlines throughout the Midwest. His father was a professor at Northwestern and his grandfather had been a president of the University of Wisconsin. After trouble at Yale University, Posey had gained a second chance at Beloit College. According to his psychiatrist, Posey’s IQ was greater than Einstein’s. After Posey pleaded not guilty due to insanity, the courts committed him to Wisconsin’ Central State Hospital for a couple of years. The state freed him in 1959 after two years on parole. He passed away in 2011.

Among those witnessing the devastating chapel fire was college presidential candidate, Miller Upton, on his first visit to campus. Upton later recalled how impressed he was by the college and community response to the fire and that their positive attitude led him to accept Beloit’s presidency two weeks later.

Beloit College rebuilt Eaton Chapel, retaining the original belltower and other exterior walls. Miller Upton’s inauguration on October 29, 1954, was the first major event held there. Rededication took place exactly one year after the fire, on December 12, 1954.