Fridays with Fred - Pearsons Hall

On a sultry evening in late June of 1893, D.K. Pearsons felt both tired and exhilarated. Commencement ceremony over, a meal with his own “class of 1893” consumed, he entered a room in old Chapin Hall especially set up for him. He’d funded the dormitory two years before. Now, as he gazed out the window, a crimson and orange sunset illuminated the sky behind his latest accomplishment, a new science hall for Beloit College.

In some ways, Pearsons was a shy man, at least when facing large crowds. He’d begged off attending groundbreaking and dedication ceremonies for even his most celebrated building. But he also liked to surprise with unannounced visits, including Commencement Day, June 21, held at Beloit’s First Congregational Church. As Chicago’s Inter Ocean reported: “After the salutatory, a rather old man was seen walking up the aisle toward the platform, and as the audience recognized the venerable D.K. Pearsons, the stanch and liberal friend of the college, the cheers were taken up in all parts of the church until the whole building rang.” President Edward Dwight Eaton recalled an earlier visit when Pearsons announced his “electrifying promise of a science building.” Eaton told those assembled that Pearsons was there to become an honorary member of the class of 1893. Outlining the benefactor’s early failure to attain a college education due to poverty, Eaton noted that after a long life and successful career, offering the standard A.B. degree would seem meaningless. “There are some honors thrust upon men which they can decline to accept,” he said, “others are theirs inevitably as the fruitage of their life. Such has come to Dr. Pearsons, and I but indicate the degree which is universally and gratefully acknowledged to be his when I record him as having attained the degree, not of A.B., but of C.B. – College Builder.”

Why was the construction of a new science hall so crucial to the college? Beloit’s early curriculum was modeled on that of Yale’s, classics-based, with strong emphasis on Latin and Greek, ancient history and literature. At first, students had to wait until their junior year to sample science, which included botany and astronomy, with zoology, mineralogy and geology offered the next year. As the college grew, its faculty and curriculum expanded, but there were no majors. Students followed a “Classical Course” or a “Philosophical Course.” By the early 1880s, the cash-strapped college met a growing interest in the sciences by fixing up a wood frame dormitory, then known as South College, as a laboratory, but it was clearly inadequate. Already a famous geologist and educator, Thomas C. Chamberlin, class of 1866, urged the college to update its science curriculum, “apparatus,” and facilities. Then, after D.K. Pearsons offered his first major gift, a way seemed to open.

Pearsons helped fund the construction of old Scoville and Chapin Halls. In 1891, President Eaton wrote to Pearsons, hoping to convince him of Beloit’s desperate need for a modern science hall up to the standards of the best Eastern colleges and universities. On June 22nd, Pearsons replied, “I will now close the trade and build Science Hall…I accept the plans and amount to be expended.”

With money secured from Pearsons and others, the college hired the Chicago architectural firm, Burnham and Root, to draw up plans. John Wellborn Root had passed away in January, while the firm developed architectural designs for Chicago’s World’s Columbian Exposition, set to open in 1893. Daniel H. Burnham carried on as the master architect overseeing construction of the Exposition, later dubbed “the White City.”

The college chose a site formerly used for impromptu “base ball” contests. The building’s rear overlooked the Rock River, while a wide lawn spread out in front, a future student hangout on pleasant days. At the groundbreaking, students helped pull the plow guided by first president, Aaron Lucius Chapin. Then, on May 12, 1892, a crowd gathered in the sunshine behind brick and stone rubble, the waist-high outline of a brick wall, and a massive stone block with an ornate “1892” carved on it. Professor Thomas A. Smith orated about the history of scientific instruction and then President Eaton marked the laying of the cornerstone. Professor Charles A. Bacon’s hymn, written for the occasion, concluded with the words, “Science true and faith’s pure trust.”

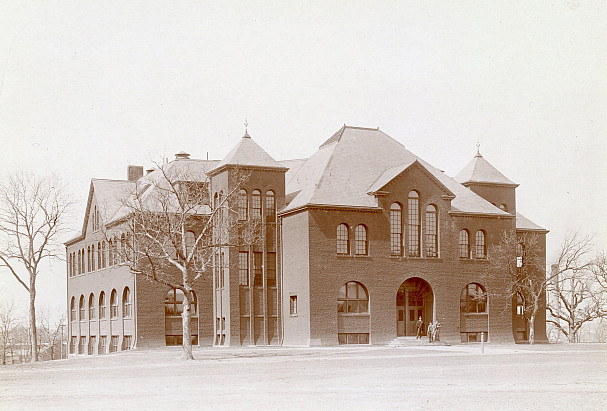

Over the remaining months of 1892, students watched the walls rise. The Romanesque Revival Science Hall looked nothing like the other campus buildings. The Round Table remarked that students seemed initially disappointed “at the bare and almost barn-like appearance of the design,” but eventually came around to its “beauty and taste.” The writer continued: “The rich dark brown of the brick is not only unique but presents a delightful contrast to the white and red of the other buildings. And then you notice the outer face of the brick is not smooth like ordinary brick, but is broken as if it were rough-hewn. This gives a delicate play of light and shade which greatly enhances the beauty.”

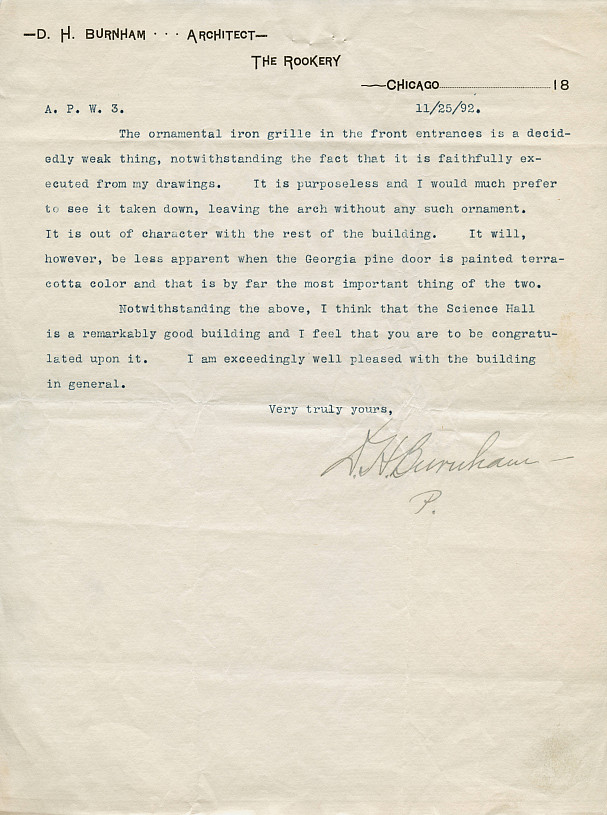

As Science Hall neared completion, architect Burnham offered a lengthy critique. Among other complaints, he regretted the “rough finish” of the building’s Georgia pine ceilings and especially “the ornamental iron grille in the front entrance, which he called “a decidedly weak thing, notwithstanding the fact that it is faithfully executed from my drawings. It is purposeless and I would much prefer to see it taken down, leaving the arch without any such ornament. It is out of character with the rest of the building.” College officials must have disagreed. The ornamental grille holds fast to the arch to this day.

On January 13, 1893, the Round Table reported on Science Hall’s dedication: “To-day is one of the festal days of Beloit College. It marks a great step in our progress…To-day we have dedicated the largest and most complete building which adorns our campus…Henceforth science may be pursued in Beloit under the most favorable conditions.” The college named the building Pearsons Hall of Science, after its friend and benefactor.

D.K. Pearsons and others had also provided funding for scientific equipment. The college catalogue included the building’s floor plans as well as detailed writeups on each department and its equipment. Among others, Physics boasted a Meyerstein spectrometer and Babinet compensator, Geology, a petrographical laboratory, Biology, dozens of microscopes, microtomes, and an aquarium, and Chemistry, laboratories “stocked with the best refined chemicals, balances, and apparatus.” Pearsons Hall also hosted the college museum, which featured “collections in the departments of Zoology, Mineralogsy, Palaeontology, and Archaeology.” Eventually, the growing Archaeology collection moved to Memorial Hall, where it became known as the Logan Museum of Anthropology.

Pearsons Hall served the college well into the 1960s, when once again it became clear that Beloit needed a modern facility for the sciences. After the college dedicated Chamberlin Hall in 1968, Pearsons became semi-mothballed, housing the college print shop and computer center, offices for professors, storage for theater scenery, and more than a few sleeping bats. By the early 1980s, dealing with severe leaks and decay, the college erected a chain link fence around Pearsons, barring all but the most daring students. There was talk of tearing the building down, despite its storied history and connection to a renowned architect, which placed it on the National Register of Historic Places. Happily, through the efforts of President Roger Hull’s administration, Pearsons underwent renovation and emerged as Beloit College’s Jeffris-Wood Campus Center in 1985. As a tip of the ol’ top hat to one of Beloit’s champions of long ago, the college dubbed its snack bar, “D.K.’s.”