Fridays with Fred - A Pioneering Environmentalist: James J. Blaisdell and Beloit’s Big Hill

On a warm, sunny Sunday in 1837, one of Beloit’s founders, Lucius G. Fisher, climbed up to the bluff where the college now stands and gazed at the lush landscape before him. “I had an uninterrupted view of prairie such as I had never had before,” he wrote, later. “I said to my friend with me that it was the most beautiful landscape that I had ever seen…”

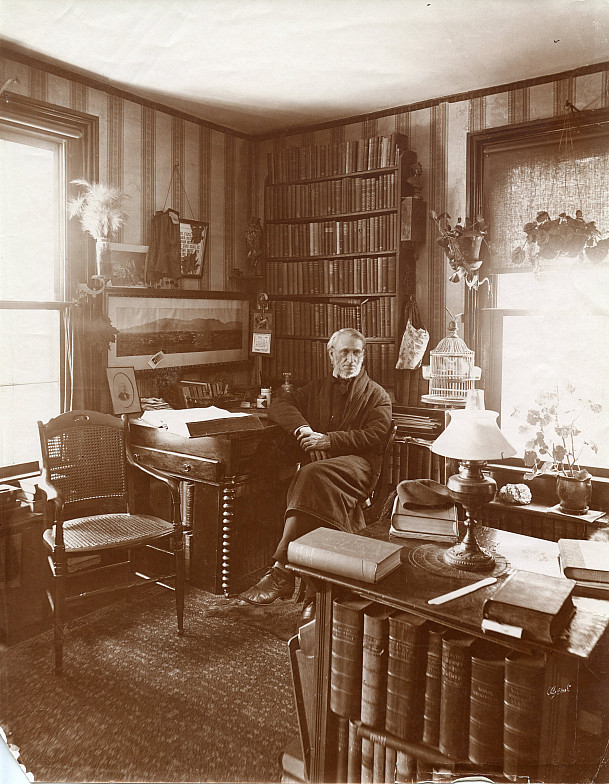

Just over 20 years later, in 1859, newly arrived Beloit College Professor of Mental and Moral Philosophy, James Joshua Blaisdell, also fell in love with that view. Yet during his strolls along the bluff, he witnessed a city relentlessly expanding – businesses lining the riverbanks, smoke puffing from factory chimneys, and houses multiplying. Around the perimeter of the city, countless farmers chopped down trees, plowed up the rich prairie sod, planted crops, and kept livestock. Beloit’s founders had set aside a little land here and there as well-groomed city parks, but citizens who sought to commune with nature in its wild state had to travel farther and farther afield.

No doubt, when Blaisdell ambled along campus paths, pondering profound philosophies or the latest student hijinks, he’d sometimes cast his eye north at the distant, steep hill rising above the Rock River. Solitary hikes across the river led him to that alluring spot, which offered both majesty and mystery. Over several years, and at considerable expense (considering the meager salary pioneer Beloit College paid him), he purchased nearly a dozen acres of the densely wooded land which later became known as Big Hill Park. Blaisdell’s son believed that, all along, his father hoped that the purchase “would ultimately be a public possession.”

Blaisdell was a quiet, contemplative man, who loved the out of doors. He’d grown up in Lebanon, New Hampshire, where, as a biographical account from 1889 noted, he gained a “free and abundant association…with nature…It was his contentment to trudge and live amid its mountains and forests, its lakes, its brooks and springs in all seasons of the year…” Although a man of diverse interests and accomplishments, he brought that deep and abiding passion for nature to his teaching and writing. His 1887 essay entitled, “The Education of the Citizen Farmer,” declared: “The man who lives among the scenes of nature has some special advantages for the cultivation of intelligence.”

In particular, Blaisdell felt passionate about the “deep woods” and their proper management. He decried what he called “methods of barbarism” toward the land and its natural resources. Blaisdell asserted, in his 1893 address, “Forest and Tree Culture in Wisconsin”: “The strain of life is growing heavier…As we go forward and wrestle with our great destiny we shall need the forests of Wisconsin, tended, beautified, replenished, cherished. Let us give them to ourselves and to our children as a great benediction.”

What Blaisdell discovered on that magnificent slope downriver, was land that had survived glaciation when the ice halted 10 to 12 miles north of the park. By the mid-19th century, the dolomite hill featured oak savanna – white and black oaks, mainly, but with bur and chinquapin oaks and shagbark hickory, basswood, elms and sugar maples, too, and with the understory a lush carpet of wildflowers. The remnant forest was a haven for birds and other wildlife. The marshland adjacent to the Rock River teemed with waterfowl, water-loving mammals, soft-shelled turtles and snappers. With his little-bit-at-a-time purchase of Big Hill land, Blaisdell preserved it from destruction, ultimately providing a gift we still cherish today.

Long before it was an official city park, Big Hill was a popular destination for nature lovers and picnickers. Beloit College students frequently boated or canoed to what one scribe dubbed, in a 1913 Round Table article, “that colossal cumulus of limestone, known as Big Hill…” The college also sponsored annual “Big Hill Day” celebrations between 1906 and 1927, which boasted a variety of amusements, including horseshoe throwing, broad jumping, a faculty egg race, a tug-of-war contest, hare and hound races, sack races, potato races, and “class stunts.” Victors of the athletic contests would win “crowns of autumn leaves.” A hearty picnic would follow. And, in the early years of the 20th century and for many years after, Beloit College professors took their students on academic field trips to Big Hill. For example, Professor Hiram Densmore’s class in plant morphology studied mosses, liverworts, and other native plants, and Geology professor Monta Wing’s students scoured the old quarry for fossils.

The city established Big Hill Memorial Park in 1926, after 4,000 Beloit citizens helped purchase 76 acres, adjoining a dozen acres donated by the Blaisdell family. Clearly, the preserve for birds and animals and budding naturalists would have given James J. Blaisdell, who died in 1896, abundant joy.

My own love affair with Big Hill Park dates back to the mid-1980s, when I first visited it on a spring field trip in Professor Dick Newsome’s Environmental Biology class. We hiked up and down winding paths and all the while Dick called out magical words as we passed by plant after plant poking up through last fall’s brown leaves – dutchman’s breeches, trillium, rue anemone, may apples, hepatica, jack-in-the-pulpit. I was hooked and have made countless visits ever since. Beloit College’s most recent ties to the park include collaborative work with the Welty Environmental Center, named in honor of longtime Beloit College biology professor and renowned ornithologist, Carl Welty. Students recently created interpretive signage at the park focusing on its history, habitat, and biological diversity. Students also continue to serve as educational interns at the center.

Big Hill Park is surely one of Beloit’s crown jewels, a truly enchanting sanctuary, in whatever season. As pioneering Beloit College environmentalist and philosopher, James J. Blaisdell, wrote in 1893: “This is what Wisconsin owes to her busy and tired children, and to the wayfarer from afar – to keep her forest glades sacred to weary feet and overstrained hearts.”

Share:

Open gallery

Related Stories