Fridays With Fred: Velma Bell and Beloit

“For the first time in the history of the Beloit chapter of Phi Beta Kappa – and that extends back some 18 years – a colored student has been elected to membership. She is Miss Velma Bell of Beloit, graduate of Beloit high school, and a student of remarkable attainments. Miss Bell has received no grade lower than a ‘B’ during her college course and has amassed so many gradepoints that she will have almost three times as many as she needs by the time she is graduated in June. She has earned almost all of her way through school in addition.” – The Beloit Alumnus, November 1929

Velma Fern Bell was born in Pontotoc, Mississippi and came to Beloit with her family in 1914. It was a period when African Americans were migrating from the South to work in Northern factories, and Fairbanks-Morse and Company of Beloit hired many laborers from Pontotoc, including Bell’s father, Walter. The family eventually settled on Elm Street on the west side, and Bell attended various Beloit schools. “I went on to high school after 9th grade,” she said in a 1996 interview, “and one of the teachers there…said to me, ‘I hope you’re going on to college.’ I remember that. And of course I had assumed that I would. It never occurred to me that I wouldn’t, but no teacher had ever said that to me.”

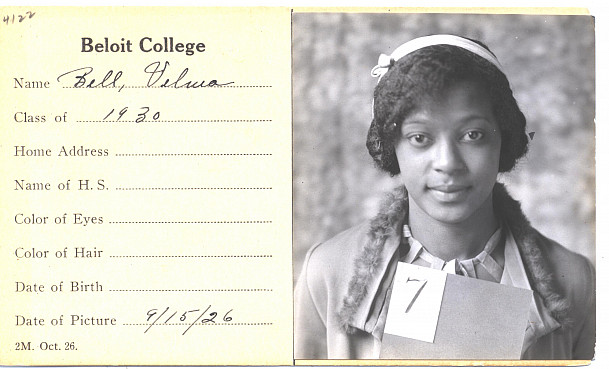

She graduated from Beloit High School in 1926, one of the top five students of her class and a member of the National Honor Society. Due to the economic climate of the times she was unable to go away to college as she hoped and so she attended Beloit, walking across the bridge to campus each day. She immersed herself in her studies and found work taking roll for the thrice weekly chapel and vespers services.

“Opportunities to develop leadership skills open to most college students were limited for me because I was a ‘townie’ and lived on what was then the ‘far west side’,” she wrote in 1985. “After classes, library study and required college activities such as chapel and vespers, I went home and did not return to the campus for recreation, student government, or social participation in small student groups (nor was I encouraged to do so).”

Tuition expenses grew beyond her means and she found it difficult to find meaningful, well-paying work, according to a January 1929 letter to the college. “During the summer the only work open to girls, of my race, especially, is housework which, as you know, is not very remunerative. Although I have received all of my education in Beloit – from first grade to college – I seem to be thought unworthy to hold the positions which my friends hold…” The college was determined to do what it could and arranged a small scholarship, followed by successful application to the Julius Rosenwald Fund on her behalf, which helped fund her junior and senior years. A letter of support by Professor Lloyd Ballard described Bell as “a student of marked ability and of genuine earnestness.”

By the fall semester of her senior year, Bell’s reputation as one of Beloit’s finest students was firmly established. That October, Beloit College Dean William Alderman wrote to Bell, “It gives me great satisfaction to be able to be able to extend to you my congratulations because of your election to Phi Beta Kappa. This coveted honor was in your case a much merited one. In these days of unsolved problems those who have minds to discern and wills to execute will inherit a great responsibility. I shall follow you with expectation as you go on to further preparation and as you finally take your place in and make a place for yourself in the work of the world.”

As part of her sociology major, Bell wrote a brilliant thesis entitled Race Prejudice, which gained her departmental honors, one of only six students honored college-wide that year. “The cry of the Negro is one with that of all the darker peoples,” she wrote. “They want freedom from economic exploitation; they want to participate in whatever economic system touches them on the basis of their merit as individuals; they want freedom from political dominations; they want their real interest represented in whatever government rules; they want an education, not one which will fit them for a certain subordinate status, but an education that will fit them to make a living in the world as it is; they want the stigma of inferiority lifted from them so that they may be able to walk down the streets of the world and into the common gathering places of mankind free from contempt. They ought to have unfettered opportunity for the realization of these hopes. Should such attitudes and desires be treated with unreasoning, intolerant prejudice?”

On June 16, 1930, after only three years of study, Bell graduated from Beloit College magna cum laude.

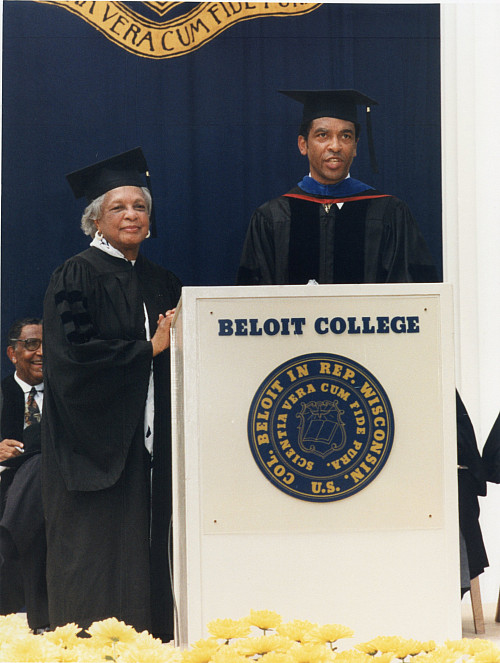

A 1985 letter commemorating the anniversary of 90 years of women at Beloit College found her reflecting on her student years: “We came along after the first women had proved their intellectual competence (which many had doubted when women were first admitted) and their abilities to enhance the quality of college life. But equally important, we were in on the ground floor of new choices and new opportunities brought on by cultural and social changes. We were exposed to a broad base of knowledge; we were acquainted with the elusive nature of truth and the need to continually search for it; we were taught (hopefully) to think, to expect and accept change; it gave some of us the successful experience of breaking down barriers; we had opportunities to develop confidence in ourselves through academic achievement. This kind of environment during my four years at Beloit was for me the ‘open sesame’ for whatever I have accomplished since graduation.”

Velma Bell Hamilton passed away on July 9, 2009 in Atlanta, Georgia.